I don’t remember when I first heard about Harry Potter. I was fairly little. It had to do with witches and magic so I remember some other kids at church weren’t allowed to read it.

At some point, I read the first book and eagerly watched the first couple movies on TV, but I wouldn’t say I was a huge fan.

Recently, at the encouragement of my wife—who is a huge fan—I read the entire Heptateuch of Harry Potter novels, plus Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, Quidditch Through the Ages, The Tales of Beedle the Bard, and The Cursed Child play. Then I watched all eight of the movies. Then read a whole bunch of stuff on Pottermore (apparently my Patronus is a wolf!). Then I watched the new Fantastic Beasts movie.

Of course, at some point along the way, I researched to see if there were any Harry Potter board games, and found… not much. Harry Potter Trivial Pursuit. Harry Potter Uno. Two versions of Harry Potter Clue. Some other long out of print and not very exciting looking games.

Then a new Harry Potter game was quietly announced: Harry Potter: Hogwarts Battle, “a cooperative deck-building game.” I had a number of reactions, ranging from “Those screencaps look like bargain-basement trading cards” to “Is this a trap to ensnare me?” to “It doesn’t matter, this could be the one.”

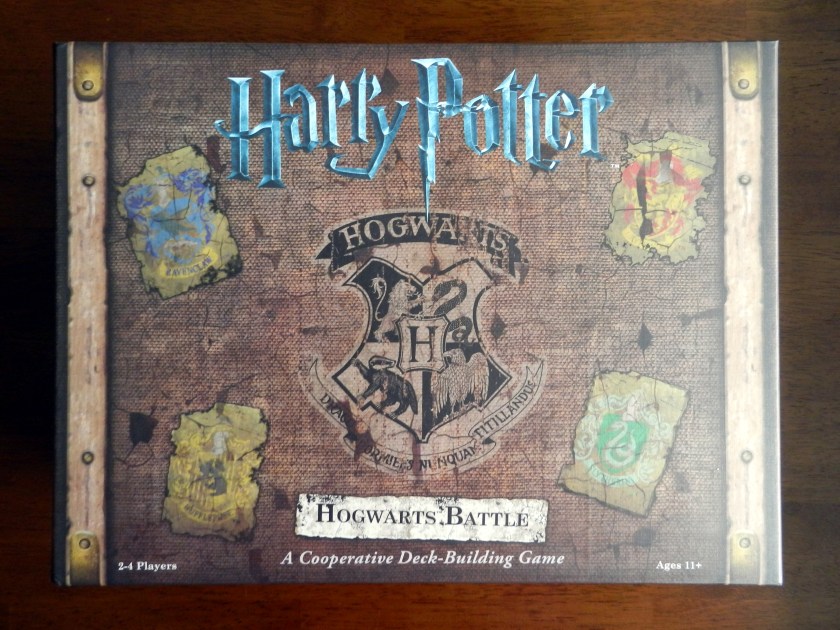

Harry Potter: Hogwarts Battle

Harry Potter: Hogwarts Battle is game for two to four players from USAopoly—noted publishers of a million different licensed versions of Monopoly who actually publish a lot other games, even though their name doesn’t sound like it. Players take on the characters of Harry Potter, Ron Weasley, Hermione Granger, and Neville Longbottom, working together to defeat villains.

Players start the game with a small deck of spell, item, and ally cards. Each turn, one player flips over Dark Arts event cards to simulate villain attacks, then plays a hand of cards from their deck to generate health points, attack points (for attacking villains), and coins (for buying more powerful cards for their deck). If the players can defeat all of the villains before the locations in the game fall to the Dark Arts, the players win.

The kicker is that inside the game box are seven smaller boxes corresponding to the seven novels in the Harry Potter series (and seven years of the characters’ educations at Hogwarts). You start with the first box, and then open a new box each time you win. Each box contains new locations and adds more villains, more cards, and more complexity to the game. Every card says which box it came from, so once you’ve finished all seven games, you can reset back to the beginning, or continue playing game seven.

Difficulty

I wasn’t sure what to think when I first saw Hogwarts Battle. Part of me thought that maybe it would be a bit too complex for my tastes, part of me thought that maybe it would be too simple.

But it’s fun! The progression of years is extremely enjoyable.

The first game is essentially a tutorial with weaker villains and only basic items available. Later games introduce more powerful villains, as well as more powerful allies, items, and spells. Everything in the game should be familiar to any Harry Potter fan, with allies like Hedwig and Hagrid, items like chocolate frogs and Nimbus 2000s, and spells like “Accio” and “Wingardium Leviosa.”

The cooperative nature of the game makes it great for kids or families. Although there’s quite a lot going on by game seven, it is all introduced in stages, which makes the game quite easy to learn. Also, contributing to the cooperative spirit, players cannot die in the game (if you lose all of your health points, you have to discard half your cards and give more control to the villains, but you go back to full health on the next turn).

My wife and I played through all seven games as Harry and Hermoine, only losing one time. This made us suspect that Hogwarts Battle is fundamentally quite easy (the game contains rules for how to ramp up the difficulty, if you so desire). However, in subsequent plays with different numbers of players and combinations of characters, we have lost quite a few times. Each of the four characters has slight differences, including different starting decks of cards. It feels like Harry is the most powerful, followed by Hermione, then Neville, then Ron.

There is a lot of variety in the game. What order the villains appear will significantly impact your chances of victory because certain villain combinations are much more devastating than others. Additionally, by game seven, the deck of cards available for purchase will be quite large, meaning you won’t see every card in every game, or necessarily come across the best cards for your situation.

Initial games are quite short, probably around 30 minutes. By the seventh game, it is considerably longer, potentially as long as 90 minutes.

Components

The production of the game is pretty close to jaw-dropping. The outside of the box looks like a suitcase (reminiscent of Newt Scamander’s suitcase, but maybe it’s supposed to be Harry’s trunk?). When you open it up, you’ll see the back of the game board, which looks spectacularly like the inside of a suitcase. Underneath the board is a smartly configured insert with compartments for everything.

The nicest bits in the game are metal tokens with the skull from the Dark Mark on them, used to show how much control the villains have over the current location. The other tokens in the game are thick cardboard. Some reviews have criticized the quality of these tokens—and metal coins and counters would absolutely be an improvement—but the cardboard ones seem durable enough and have the advantage of colored graphics that match the symbology on the cards.

The game’s cards are adequate, but not linen-finished. They seem to hold up well to the repeated shuffling that you have to put them through.

About spoilers

There are several ways that spoilers come into play in Hogwarts Battle. If you’ve never read the Harry Potter books or seen the Harry Potter movies, this game is going to spoil them right off the bat because one of the villains you face in the first game is a character whose villainous nature is a plot twist.

Also, I wish the game did a better job of keeping its own twists a secret.

Hogwarts Battle includes card dividers for sorting out the cards and storing them in the box. However, the initial stack of dividers includes one for a type of card that you don’t actually get until one of the later boxes.

Also, the back of the box shows a component list, which includes a component that you don’t get until one of the later boxes.

I really enjoyed speculating about what would be in future boxes based on the novels and then finally opening them and seeing all of the exciting new cards. The designers obviously attempted to avoid some spoilers; I’m just not sure why they didn’t go further and keep the contents of every box a secret. It would have improved the experience if the game had kept everything completely hidden from you until you get to it.

Minor complaints

I do have a few small complaints.

There are two sections in the box for cards. One of them is exactly the same size as the large cards, so the cards always fall over and are really hard to pry out.

Also, every card in the game makes total sense… almost. Dumbledore is aloof but powerful. Dobby is awesomely helpful. Dolores Umbridge is just the most infuriating. However, the Arthur Weasley card gives everyone two coins. What? I’m sure Mr. Weasley would give you his last bronze Knut if you needed it, but whole thing with the Weasleys is that they don’t have a lot of money. This doesn’t add up.

Also, it seems like they should have called the games “Year 1”, “Year 2”, etc. instead of “Game 1”, “Game 2”, etc. to take the Harry Potter feel up a notch, but maybe licensing issues came into play.

I kind of wish there was more than one playable female character, too. But that’s down to the source material because Luna and Ginny are younger, so it wouldn’t make sense for them to be going through the same seven games.

Honestly, my biggest annoyance with Hogwarts Battle is that there are a number of amazing sounding promotional cards—like the Basilisk fang—that appear to be basically impossible to get. That drives me crazy! Publishers, why do you torment me so?!

Final thoughts

One theme of the Harry Potter series is learning. At the start, Harry, Ron, and Hermione are children and Harry has zero knowledge of the Wizarding World. Over the next seven years, they grow to be powerful wizards. Hogwarts Battle doesn’t have a spatial element to make you feel like you’re roaming the halls of Hogwarts, taking a trip to Hogsmeade, or flying a car into the world’s angriest topiary, but it does feel like you’re going on the same journey of growth as the characters, facing new and more difficult challenges each year.

If you love Harry Potter as much as Romilda Vane—or even if you’re just a casual fan—there’s a good chance you’re going to love this game, too. If you don’t know a bezoar from a pensieve, you would probably still enjoy the game, but you might not get as much out of it. On the other hand, if you detest magic as much as the occupants of Number 4 Privet Drive… well, you’re probably not reading this anyways.

After playing Hogwarts Battle, it is apparent that what the designers tried to do was make the best and most comprehensive Harry Potter board game to date. It is also apparent that they succeeded. If that’s what you’re looking for, this is the game.